A short piece of fiction and second prize winner for The Short Story Net

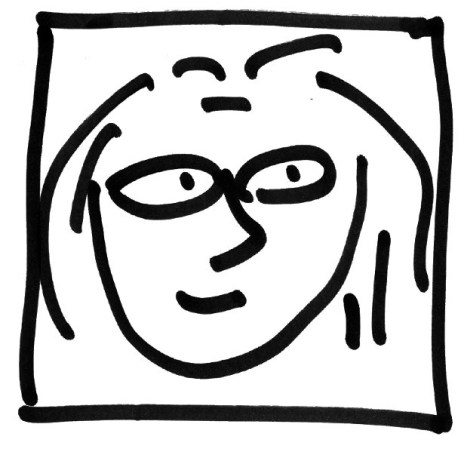

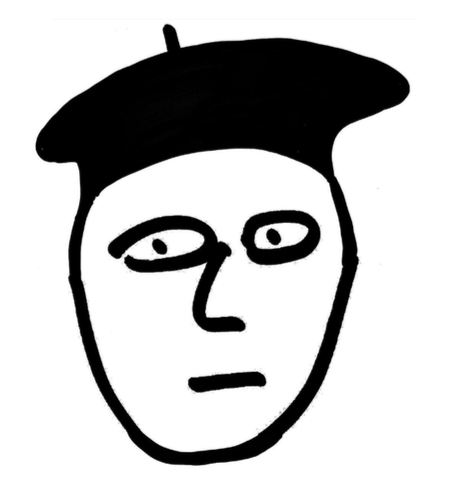

When I was eighteen, my therapist told me that every day I should draw a picture of my face.

“Don’t think about what you’re doing,” he said, “and don’t try to be an artist. Take only a few seconds, look back at what you’ve done, and ask yourself: what does this mean?”

I was a bit sceptical about this idea, because wasn’t he supposed to be the one to tell me what it means?

But this is what therapists do: they ask you what’s wrong, why it’s wrong, and what you should do about it. You do their work for them. That’s what you pay them for.

“And don’t forget,” he said, “you should write the date on the back of the pictures and keep them in a folder.”

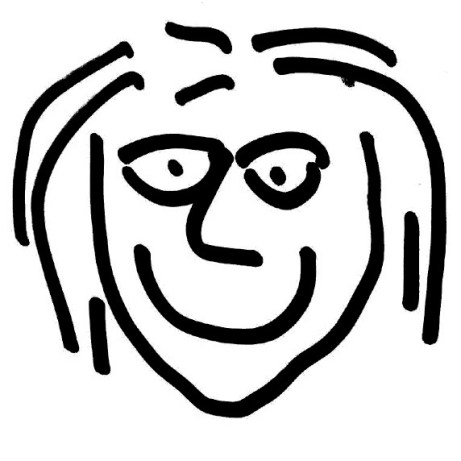

In front of him, I drew this:

“I think I’m sad,” I told the therapist.

“Yet you realise you’re sad,” he said, “which means we’re getting somewhere.”

After a few weeks, I didn’t feel any better, so I stopped seeing the therapist.

But for some reason, I kept drawing a picture of myself every day.

I didn’t know what I wanted to do at university. But I liked French and I liked Drama so I went through a guide to all the courses available at every college until I found one which offered French and Drama.

I was accepted, and moved to a new town to study.

As soon as I started the university, I realised it wasn’t a good place to learn very much of any value, and I didn’t improve my French, nor did I learn how to act, direct, design sets or anything really.

But I did find out about French Drama, which is very good, as there are loads of great playwrights such as Molière, Feydeau, Giraudoux, Jarry and Genet.

When I left university, I had to find a job. I went for interviews at a furniture warehouse which had an opening for a secretary, a hotel looking for a night receptionist, and a pig-feed firm that needed someone to type accounts into a computer.

When they asked me what I’d been doing for three years, I told them about my degree.

“You’d be surprised,” I said. “There are loads of great French playwrights, such as Molière, Feydeau, Giraudoux, Jarry and Genet.

“They say so much about life.”

I didn’t have money or work, so I moved to London. At first I stayed on a sofa in a friend’s flat, and eventually I landed a job at a wine importers, which I thought would be fun. I liked wine and I could speak French, and I expected to travel to France a lot.

But I only wrote the names of wine bottles on a spreadsheet.

The importers just needed someone who knew where to put an  and a

and a![]() accent on an ‘e’, as this was really important.

accent on an ‘e’, as this was really important.

At work, there was a guy who sat next to me who’d also studied French at some point, although he couldn’t speak it very well. His name was Mark and he talked a lot about TV programmes.

Mark was quite good at recommending series that I might like. When I bought or rented the videos, I sometimes enjoyed them.

After a few weeks of figuring out I was kind of into what he was into, he said: “Why don’t we watch them together?”

One night in his flat, we got drunk on Cabernet Sauvignon, and saw a drama or a comedy about vampires, a love affair or cops, I can’t remember, and he leaned over and kissed me. We had sex, and after a week we found ourselves going out with each other.

As we both lived in London, which was very expensive, and we didn’t have much money, we thought we should probably move in together.

I was happy that I didn’t have to live on someone else’s sofa anymore, and Mark seemed really enthusiastic about the idea. We found a small flat that was just a living room and kitchenette, with a door to a bedroom.

The day of the move was hard as Mark owned a lot of stuff. I had only a few suitcases as I’d left most of my things at my Mum’s. By the evening, we were very tired, so we left the boxes untouched. But Mark said he had to unpack the television and video, which I helped him do.

“Is it OK,” he said to me, “if you stay in the bedroom for half an hour, because I need to watch some pornography?”

I closed the door and sat on the bed. It was not yet made up, as I hadn’t taken out the linen and the duvet, so there was only a mattress. The suitcases of my clothes and boxes of his records were stacked up all around me.

After a few months we started arguing and after a few years we continued to argue. But we still lived and worked together, and we even went on holiday, once to Wales and twice to Dorset.

One evening, I was talking to my Mum on the phone, and she was quizzing me on how it was going with Mark. I went “it’s fine” and “maybe he’s in line for a promotion” and “this flat is just temporary”, and then she asked me:

“So when will you take the next step?”

“What are you doing?” said Mum. “Why aren’t you answering me?”

I put down the pen.

But I was a bit annoyed with her, because I hadn’t yet drawn my hair.

During the next month, I left my boyfriend and my job, and I lost my home. One evening I came back to the flat to pick up a few clothes that I’d left in the wash basket, and Mark was a bit drunk.

He told me: “You shouldn’t move out” and “You’re a slag” and “You were never good in bed”.

I needed a retort. A brilliant comeback. So I said to him:

“Well, it takes two to tango!”

As soon as this phrase left my mouth, I realised that when you’re in an argument and you shout at someone the words ‘it takes two to tango’ it can never sound very menacing, even if you’re in a total rage.

I thought about how ‘it takes two to tango’ would sound in French: «il faut être deux pour danser le tango».

This was mean and passionate, but a bit stiff.

I don’t think Jarry would have ever said it, or Genet. Perhaps Feydeau.

No, not even Feydeau.

I stayed on a friend’s sofa, and I needed another wine importer job where it would be very important to know the difference between an  and a

and a accent on top of an ‘e’, but I didn’t find one. I searched for some work translating, but there are lots of people who know French in London, and there are lots of French people in London, and I hadn’t been to France for eight years because Mark didn’t like French food, and he wasn’t very keen on the French people.

accent on top of an ‘e’, but I didn’t find one. I searched for some work translating, but there are lots of people who know French in London, and there are lots of French people in London, and I hadn’t been to France for eight years because Mark didn’t like French food, and he wasn’t very keen on the French people.

It was an interesting time.

I guess I was doing something.

One night I wanted to stay somewhere familiar, but not at my Mum’s, and I went back to the flat where Mark was still living, and I got drunk and slept with him.

I stayed.

One week later, we were sitting on the sofa watching a comedy series about the Romans that wasn’t very funny, but Mark thought it was hilarious and he was laughing loudly.

I stood up in front of the TV and said to him:

“I really have to leave this time.”

I packed my suitcase and headed for the door. He looked over his shoulder at me from the sofa, and waved his hand.

“See you around!” he said.

I went to my Mum.

For a month I didn’t draw a picture of myself.

One morning my friend Fiona called me and said she needed someone to work in a gallery she was running on a posh street in the centre of London.

“I’ll do it,” I said.

“Great,” she said, “but we’ll have to get you dolled up.”

I took the train to London, where I met Fiona, and she took me to a salon.

The salon cost a lot of money and I thanked my new boss.

“I will take it out of your first week’s pay,” she replied.

I wondered if Fiona was really my friend, but I needed the job.

People expect a gallery to be really cool and for lots of celebrities to visit, but few people came in. So I sat all day on a computer, and I was nice to the customers, and sat more at the computer, and I couldn’t surf the net or play games because someone might see me, so I was just staring at the screen.

The most regular visitor was this old guy who looked at me more than he did at the pictures. He was smart and well-dressed and we got talking, and he asked if I wanted to go for a drink. I waited to get the OK from Fiona first, and she said that the same guy asked her out once, but I don’t believe she was telling the truth.

His name was Peter and he used to run a company that made computer software, which he sold for a lot of money. So he wasn’t doing much, but he liked art and he thought I looked bored in the gallery.

That night we went to a nearby hotel which was quite expensive, and it was cosy, and drinking at the hotel bar was really nice. Because I only ever went to pubs, I never knew that hotels in the centre of London had such cool places. I was very drunk when I got into bed with him and I don’t remember what happened.

“We should do that again,” Peter said the next morning.

“Maybe,” I said.

We went out four times over four weeks and one day he said we could go to his house, which was not far from the gallery. I thought it was strange that he invited me to a hotel, and then to his place, if they were so close to each other. It was a nice townhouse, and inside was a small living room with toys scattered everywhere, and he hadn’t mentioned his children before.

“Are you divorced?” I asked.

“Soon will be!”

We slept together in a room which might have been where he stayed with his wife most days of the week, and I didn’t ask him, because it was fun, although I was drunk and don’t remember much.

But the next day at breakfast Peter told me: “It looks like you’ve become the other woman!”

He laughed and kissed me on my forehead, and I looked down at the toys on the floor, and wondered why he hadn’t cleared them away.

I was the other woman for a few weeks, but the bar was not so much fun after a while, and I didn’t get drunk anymore before we slept together, and I stopped answering the phone when he called, and he stopped calling, and I was quite happy that he stopped calling.

I stayed at the gallery.

In the greatest city in the world.

Where there was so much to do every night…

…cinema, art, cuisine, theatre, a Giraudoux retrospective at The National.

A couple of other guys.

My Mum called me and told me she was sick. I decided that it would be best if I left my job and went back home to look after her.

She lived in a small flat on the south coast, and spent all day in bed, except when I took her to the doctor by taxi. We started a new therapy of this, and a new therapy of that, but nothing seemed to help her do anything more than stay in bed, where she felt very tired, and threw up a lot.

I cleaned her clothes and tried to cook, but most of the time we ordered takeaway food. When she was asleep in bed, I looked at the Internet, and ate a lot of crisps and nuts and I found out how nice it was to put peanuts between crisps and eat them at the same time, as though they were a crunchy sandwich.

I was a bit bored to be honest, but I didn’t have to worry about money, and I had a place to stay.

Mostly we sat in the living room and watched TV. When there was nothing much on, she started talking about her old job, which she said was never very interesting, and not what she wanted to do, but she hated being retired even more.

One night she talked about Dad, and how he was very good looking when he was younger, and how she was lucky to have him. But he was sad after they got married, because he never had enough money. He died of cancer when I was still at school, and after that she never met anyone else.

She began to get thinner, and lost all her hair. The doctor said we can try this therapy, or that therapy, and we can get this donor, or that donor, and Mum said she was fed up with all these drugs and appointments, and sleeping all the time, and feeling useless.

She was throwing up more, and there were even fewer TV programmes that she wanted to watch. So we spent even more time talking, and she asked me about me.

“Why are you here?”

“To look after you,” I said.

“But, you’re not very good at it.”

The next day she died.

I left the house and walked on the seashore. It was Spring. It wasn’t warm. There was a wind, but no chill. This was supposed to clear my head. To give me peace. Balance. That was the aim, wasn’t it? A good blow, that was what Mum called it. When we had nothing to do on a Sunday, she always used to say: “Let’s go for a walk, there’s nothing like a good blow!”

I found a patch of sand and took off my shoes and socks. With a wet stick covered in algae, I mapped this out:

I stood on the edge and decided to throw inside everything that I didn’t like about my life. In went my studies and my jobs. My lack of a job. My relationships. My lack of relationships. The relationship with my parents. The fact that there were no more parents left for me to have relationships with, however shitty those relationships might be. All the places I’d ever lived. Every holiday I’d ever taken. My face. My hair. The way that my hands looked five years older than the rest of my arms.

The tide was moving slow and gentle, but with such stealth that I hadn’t noticed it had sucked in the sand in front of me, and destroyed one side of the square. I was perched on the remaining edge, as the swell moved under my toes.

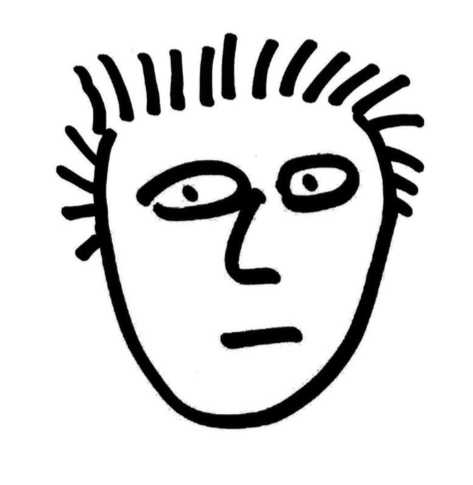

I was seven weeks into seeing my new therapist, when she asked me about my old therapist. I told her how I drew pictures of me every day, and kept them in folders for almost 30 years. She asked me to bring them all in.

So the next day we laid them out on the floor of the consulting room.

“Oh, they look like dance steps, don’t they!” she said.

“Yeah, where people walk all over my face.”

I showed her the dates on the back, and told her what happened at each particular time, trying to remember a lot of things that I wasn’t quite sure about.

“Why do you keep doing this?” she asked.

“I don’t know. It never made me happy or successful.”

“But did it make you feel better?”

“No,” I said.

She moved her eyes across the pictures.

“We should do something with these!”

“Like what?”

“Well, who do you know?”

I called Fiona. A month later I was back at the gallery. But I was not working there.

There was a launch. Fiona put together a press release about ‘a frank and honest outsider artist who has catalogued her life in portraits’, which was actually really well-written.

Some magazines and websites came to the opening and a couple of journalists spoke to me. Peter also arrived. He was thin and well-dressed, much older, but still refined.

“Hmmmm,” he said, “these faces are interesting.”

“Thank you.”

“I can really see you in them!”

“That’s… a very nice thing to say.”

“I’m in the middle of a divorce.”

“Oh, that’s terrible.”

“It’s for the best.”

I nodded.

He went on.

“We had some good times.”

“Well…”

“Didn’t we, back then?”

“If you remember the year,” I said, “I can check the wall.”

For some reason Mark came to the launch. I hadn’t told him about it, but I guess he was following the gallery online. He was fatter and balder, his eyes were red and his face blotchy, but he didn’t smell as bad as he used to, and his clothes were washed and ironed.

“I have two kids now,” he said.

“Lovely.”

“I’m very happy.”

“I am too.”

“A boy and a girl.”

“One of each.”

“It’s what we wanted.”

“I’m so happy that you’re very happy.”

From his pocket, he took out a handkerchief, which was ruddy and a bit stained, and blew his nose in front of me.

“Sorry, you know, cold.”

I nodded.

Who the hell still carries a handkerchief?

After the opening, I was in arts listings online, and a website published a small interview with me that I don’t think many people read, but it was nice about what I’d done.

For the first few days, people came to the gallery, but then the number of visitors began to drop. Fiona said the pictures could stay up until the end of the week, but she needed to start selling some art. Although a few people were interested in what I did, no one wanted to buy it.

On the last day of the exhibition, I was the only person in the gallery, except a new girl who was working as an assistant. She could surf the net and check her messages, which I hadn’t been allowed to do. She seemed bored, but slightly better off than I was.

“I like what you’ve done here,” she said. “I find it very inspiring.”

“That’s wonderful. Are you making pictures of yourself?”

“No-o-o,” she said, “because it is, at the end of the day, a bit weird.”

“So will you keep on doing it?” she asked, looking down at the portrait I’d just drawn. “I mean, like, forever?”

“Will you keep working here?” I asked.

“I doubt it,” she said.

I turned over the piece of paper, and wrote the date on the back, and handed it to the girl.

“You can have this one,” I said.

I stayed in a flat on the South Coast. I didn’t know what to do anymore. I had a bit of money, but not much. What I did have was some great ideas. In fact, I had the best ideas I had ever had in my entire life. I couldn’t wait to do something with them.

And then

What happened to

My mother

Happened to me too.

A tube entered the skin under my elbow, and it caused a bruise that was green and grey and blue at the same time. It was too painful to move my arm. I could not pick up a pen and place it on a sheet of paper.

I could only speak. There was a nurse listening. Young, thin, English with a faint Sussex accent. She asked me if I would like to write a letter to someone. It was very nice of her, and she said it in a very considerate way, which proved she had been trained with some competence. At the same time it made me feel, for the first time, certain that I was about to die.

So I said that I wanted to write a philosophical treatise. She stirred a little in her chair, and knitted her brow. It was clear she wasn’t entirely enthusiastic about this prospect, but I was glad that she hadn’t greet my request with a sigh.

And I became rhapsodic.

I think of all the writers who published books that were bestsellers in their day – the war stories of the 50s, the horror novels of the 60s, and the romances of the 80s.

No one reads these books any more.

I think of the artists, who were once exhibited widely – how images of broken industry that were so fashionable in the 70s now seem no more interesting than a bland landscape of fields, fences and sheep.

No one stops to look at a photograph or an oil painting of a derelict factory, its roof caved in, its walls black from soot, a wooden sign in fading red advertising a biscuit company long since disappeared.

But we cannot pulp the book, burn the photo or whitewash the canvass. We must give them a home, somewhere.

I pick up a filing number, take my place in the basement and join the ranks of the archives. Here it is cold and dry, musty and dark.

Although I am catalogued, handled with care, and given respectful lodgings, I have to face up to the truth that I have been abandoned.

But this isn’t a problem.

It’s never lonely to stay with the forgotten.

Thanks to everyone at The Short Story Net for their help and support