Exposing animal exploitation on the Adriatic.

Written with Ovidiu Dunel-Stancu and Damira Kalač, and published in Vijesti

Ulcinj is a sea-side resort in south Montenegro with only 12,000 residents, the majority Albanian-speaking. Yet during the summer these numbers rise by a further 120,000, as the town boasts one of the longest sandy beaches on the Adriatic, with bars, sunloungers and a funfair. According to locals, there is also something far weirder in the resort: a performing monkey, who poses with tourists for selfies and videos.

In the centre of the town is the small beach, below the old walled city on the hill. We speak to a car park attendant, and ask him where we can find the animal. He laughs and tells us “the man with the monkey” will be on the beach tomorrow at one or two pm. It’s too late now. We ask more people on the beach. Many are annoyed with our questions, and don’t know about any man with a monkey. The next day we return at lunchtime. We find no man and no monkey. We ask at a supermarket, a bar and at tourist information. They have no clue.

We ask the receptionist in the hotel where we stay. She says she hasn’t seen the man with the monkey since she was a child. Could this be a myth? we ask ourselves.

We head to the long beach, which is a 14 km stretch of sand crowded with sunloungers and umbrellas that cost 18 euro to rent for the day. Red flags are up, but people are paddling in the water. We ask a man selling peanuts about the man with the monkey. He also bursts into laughter and says: “Yeah, he walks up and down the beach all day”. We ask the lifeguard, who replies: “You just missed the man with the monkey. He may be coming back. He may have gone to another beach.”

The next morning we return to Long Beach. We ask everyone we can meet: “Have you seen the man with the monkey?”

He will come, they tell us, it is still too early. We wonder if the people of Ulcinj are all playing a joke on us.

Exhausted and disappointed, we take shelter in a café called Tony’s Grill and refresh ourselves with a coffee and a Fanta. We have wasted two days searching for this madness.

We make one last round before we leave.

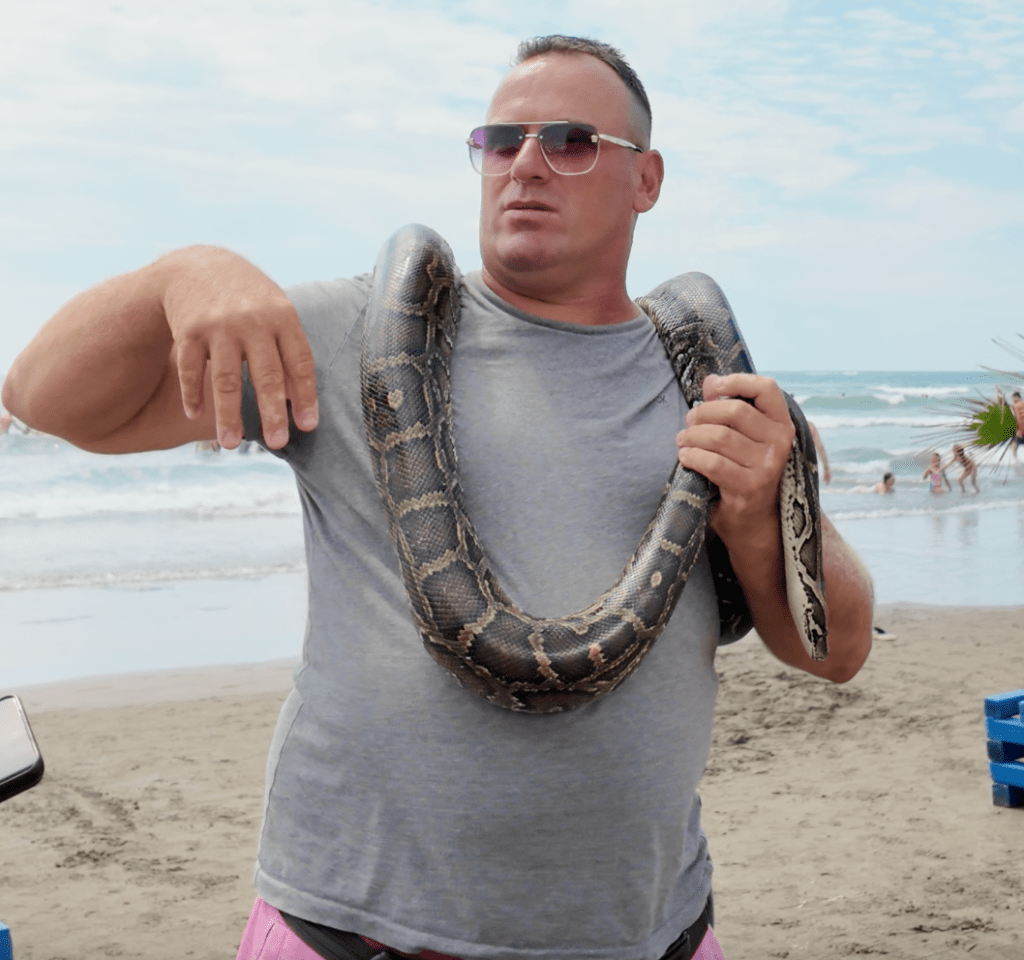

On the beach, we see a heavyset guy in a t-shirt and sunglasses, carrying a giant Burmese python.

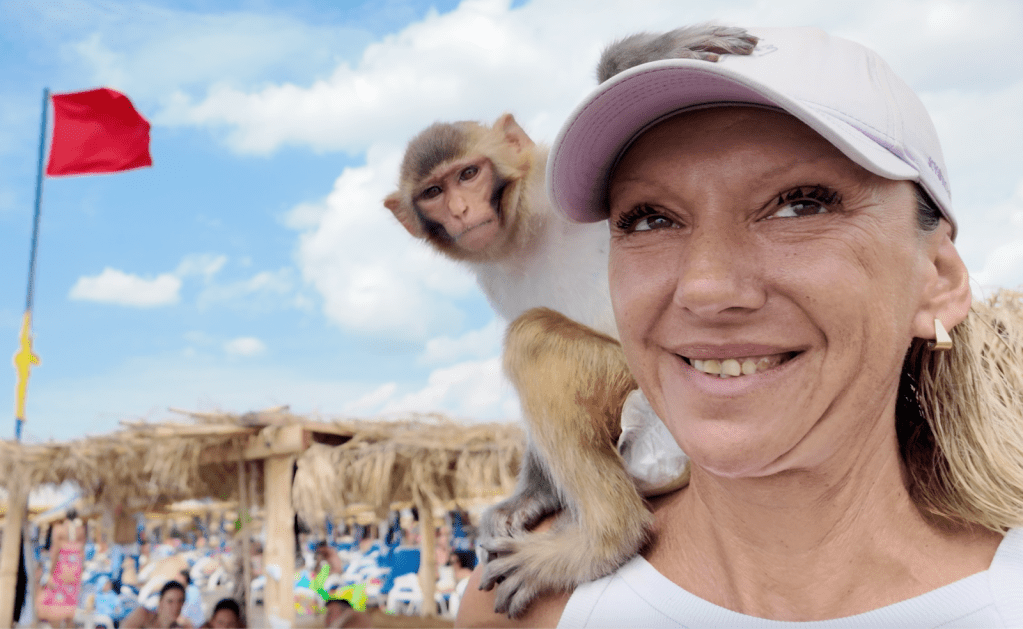

People are gathering around to take pictures. Next to him is a thin woman in her late 40s in a white baseball cap. On her shoulder is a baby rhesus macaque in a nappy.

Monkey in nappy

For five Euro, I can put the monkey on my shoulder. It tries to grab my glasses. The woman clicks at the monkey, points to the lens on our phone and says to the monkey: “Camera! Camera!”

For ten Euro we can hold the snake.

“Is it venomous?” I ask.

“No problem!” says its owner.

This does not answer my question.

I ask the woman about the monkey’s name.

“Tsiki,” she says.

“And the snake, does it have a name?”

“Snake – no name,” she shakes her head sadly. “Python. It is Python.”

Tsiki is only one year old.

“This is small monkey, big monkey is on small beach,” she says. So there is more than one monkey in Ulcinj.

Monkeys have also been seen in the more upmarket resort of Budva, and in Sutomore, a favourite seaside resort of Serbs and local Montenegrins. Sutomore’s tourist centre is a single promenade overlooking a narrow and crowded beach. We ask cafe owners and tour guides about the man with the monkey. Is it the same man: the big guy with slicked-back hair and sunglasses? A cafe owner tells us no: there is another man with a monkey. One says he is at the Habana cocktail bar every night at eight pm. When the sun goes down, the animals come out.

We wait all day and sit on a wall opposite the lounge, which doesn’t open until after dark. The street fills up with families and young people looking for food or drinks or to go to the funfair.

The walls are taken up by people selling fake perfumes and African trinkets. On tall perches sit red and blue macaws, cawing. Children try to touch them, but the birds snap at their fingers. I wonder if this is the main attraction. But people are not paying to hold the parrots. Instead, they seem to be a colourful signal. Next to the birds is a man in his 30s in a short sleeve holding a baby caiman.

Children line up to touch the animal. Next to this he has a polaroid camera, and offers pictures of the caiman for five euro.

A few metres away is another woman in her early 20s with blue streaks in her hair who keeps a ball python in a carry-case. She offers to place the python around people’s necks and in their hands for five euro. A boy, aged around three, has the python around his neck. His family eagerly take pictures with their phone.

“Does the snake have a name?” I ask.

“Yes, it has a name, Smiley.”

“Does it smile?” The predator’s face is unreadable.

Further along the promenade is a tall guy in his mid-20s with a yellow Burmese python coiled around his neck. For five euro, he let kids as young as seven put the snake around their necks.

The reptile’s name is Bella.

An “illegal” and “abusive” tourist attraction

“This breaks the law on the protection of nature,” says Stefan Šljukić, a lawyer who works with Montenegrin animal rights NGO Korina. “These animals cannot be used as entertainment in such a way. The law nowhere allows nor justifies subjecting animals to prolonged and painstaking exposure to crowds of people for photography.”

We later find out that the couple who walk up and down the beaches of Ulcinj with the monkey and the snake are Almir Alovic and his partner. Alovic did not respond to our attempts to call him on the phone or contact him through social media.

One reason could be that he has been under detention. On 5 October, officers of the Ulcinj Security Department arrested the 43 year-old, on suspicion of having committed the criminal offense of domestic violence. Following a verbal argument with his wife, she sustained minor bodily injuries, says a police report, and then made a statement to the police. He was detained for up to 30 days.

To keep such an animal, owners also need a permit from the Montenegro’s Environment Protection Agency (EPA).

In recent years, the EPA has issued permits for pythons, parrots and monkeys, mostly to individuals from Podgorica. Alovic is not among them. No permits were issued for caimans, parrots, monkeys or large snakes in Sutomore and Ulcinj. This means the animals could have been bred or trafficked illegally.

The agency told us the permits were for “non-commercial keeping in adequate enclosed facilities in accordance with legal regulations, and not for public display on streets or similar places”.

The hustlers of the Montenegrin seaside could face inspection, but there are few inspectors to cover the whole of the seaside. Montenegro’s 600,000 population swells by a further 230,000 of foreign tourists in August.

Some exotic pet owners come to Montenegro from abroad, and bring their animals with them. People also move in and out of Montenegro in the summer, and cannot be caught. A new law could come into place on nature protection, which makes illegal trafficking of animals a three to five year prison sentence. Now traffickers only pay a fine.

Seaside monkey legacy: traumatised and abandoned

But what happens to these animals after the season ends? Or if they are no longer useful?

In the mountains outside Podgorica up a single-lane road is the Shelter and recovery of animals – Montenegro, a wildlife park.

The shelter houses albino raccoons, ex-circus camels, two wolves and one bear. There are also pythons, including a large yellow Burmese python.

In a small wooden cage stays a rhesus macaque monkey. He appears twitchy and agitated. When I come close to the door, he runs away to the window and looks over his shoulder at me suspiciously. His name is Chili.

When a child nears the entrance, the macaque bangs on the walls of the cage and starts screaming.

“He doesn’t like small children,” the owner says.

Chili was abandoned here in 2022. He had spent years entertaining children in Sutomore. But then he outlived his use. Now he stays here, traumatised, shouting at children.

The owner’s mother tells me the shelter has placed five wooden bars behind a glass window, so Chili won’t bash on the glass.

There is another monkey at the shelter, a grivet monkey, which lives in its own cage, and used to work on the beaches of Sutomore.

Animal selfies “normalise wildlife exploitation”

We showed videos of the traumatised animal and the seaside monkey to the European wildlife organisation specialised in primates, AAP – Animal Advocacy and Protection.

“For tourists, getting a selfie with a wild animal often seems like an unforgettable experience,” says Katharina Lameter, AAP’s Public Policy Officer. “However, what these photos usually document is not fun or joy, but animal suffering.”

In other countries, the NGO has seen similar examples of monkeys used as “props” for photo opps, and says these monkeys are often removed from their parents at a very young age, forced to interact with strangers all day, and discarded when they become too old or dangerous to be used. This causes extreme stress to the monkeys and can drive them into unnatural and harmful behaviours, like backflips or self-mutilation.

“Photos and videos on social media also contribute to the problem, by normalising wildlife exploitation and encouraging others to seek the same experiences, perpetuating the cycle of abuse and suffering,” says Lameter.

“A true wildlife encounter doesn’t need a selfie.”

This story is part of the Animal Hustlers project – www.animalhustlers.com supported by a grant from IJ4EU